Boracay is renowned for its powdery white sand, beach resorts, and vibrant nightlife. Most tourists go here to party and unwind. But for the Ati, the island’s original inhabitants, tourism has come at a steep price.

During a recent trip, I found myself visiting Bihasin: The Ati Living Heritage Center, a small community museum that tells the story and struggles of the Ati. Located along the road in Bolabog, it’s easy to miss if you’re not looking for it. Upon entering, I was greeted by Maria* (not her real name), who led me to a native hut with a sandy floor.

The center’s name, Bihasin, is an Inati term that means “wealth” or “treasure.” This reflects Ati’s beliefs that their lives, community, and the island itself are the true sources of shared wealth.

One display recounts how the name Boracay was derived from a combination of two Inati words, bora (bubble) and bukay (sand). The Ati ancestors named it so because of the way the white and powdery sand of Boracay resembled the bubbles that form along the island’s shores.

“Dati naglalaro lang kami diyan sa White Beach pero ngayon, parang hindi na kami welcome,” (The white beach used to be our playground, but we no longer feel welcome there),” Maria told me.

Some exhibits detailed the history of early settlements, rituals, and sacred sites. The Ati traditionally lived in caves and sustained themselves through hunting, fishing, and gathering. In one corner, baskets and traditional wooden implements were displayed. A glass case displayed an assortment of shells, pottery, and relics.

Tourism started in the 1970s as early backpackers “discovered” the island. Migration brought foreigners from other countries and different parts of the Philippines, impacting the Ati’s simple and nomadic lifestyle. Because of commercial interests, the Ati were pushed back from the beachfront and forced to abandon their ancestral homes.

One poignant display pointed out: “The dark color of our skin soon made people call us dumi (dirt) on the white and fine sand of a paradise-like island.”

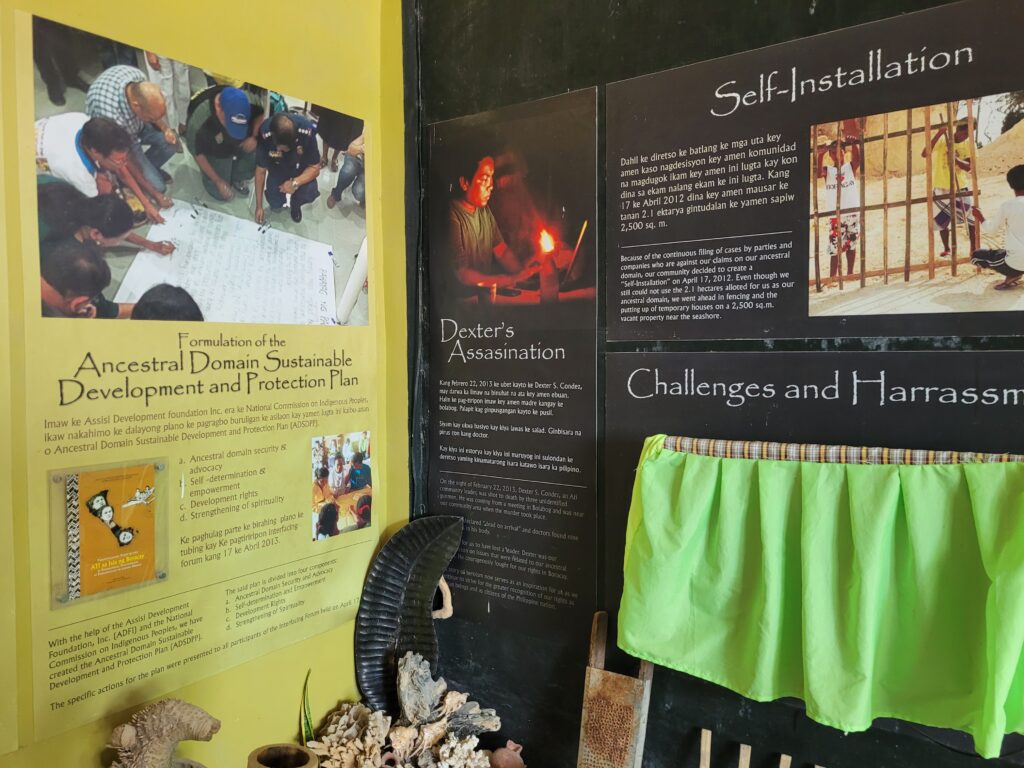

Maria shared how “parts of Boracay were sold to business people and corporations” piece by piece, which led them to establish the small community in Bolabog. “Hindi na kami makadalaw sa mga dating lugar na kinalakihan namin, mga kweba at libingan dahil sa mga bagong hotels,” (We can no longer visit some sacred sites, caves, and burial sites as access has been gated off), she said, recounting how they’re blocked by security guards outside luxury resorts. One panel detailed their struggles to reclaim their heritage and ancestral lands, including the assassination of Dexter Condez, a prominent Ati community youth leader and spokesperson. In 1997, the community united under the Boracay Ati Tribal Organization (BATO). In 2011, it was eventually granted a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) recognizing its rightful claim to a 2.1-hectare portion of Boracay. Additional land was later awarded for agricultural use, leading to initiatives such as a dragonfruit farm.

Despite this, they still live in fear of being edged out completely and lament the impact on the environment.

“Dumami ng dumami masyado ang mga resort. Dati wala ka na malakaran sa beach, kulang na lang ilagay nila mga mesa sa dagat,” (The number of resorts just grew. There was a time, you could barely walk along the beach, they might as well have put tables in the water), she said, describing the situation before the massive island rehabilitation in 2018 and pandemic closures somewhat slowed down development.

While there’s no entrance fee to visit, donations are accepted. As a way to preserve their identity and generate income, they’ve also embarked on livelihood programs offering handicrafts, bath soaps, and other items for sale.

Exiting from the back of the village took me to a tiny beachfront cove where Ati kids were playing next to boats. Compared to the bustling atmosphere of White Beach, Bolabog still feels calm and peaceful for now. But as I watched windsurfers catching waves, I felt a sense of dread, seeing how upscale hotels have already crept up along the stretch and large structures looming in the hills.

The Ati believe that tourism and development shouldn’t come at the expense of the natural environment. If only all businesses felt the same way.

Bihasin: The Ati Living Heritage Center is located in Boracay, Aklan, Philippines.