Let me tell you about an invisible mall.

In August 2002, a fire tore through Kimball Plaza, the biggest mall in General Santos City (GenSan) back then, and when the smoke cleared the damage came to about a billion pesos. It was the worst fire the city had seen in living memory. The blaze took out nearby shops too, and to this day no one really knows how it started. Was it an accident? A terrorist attack? (People wondered about that especially since the mall had already been bombed just four months earlier in April, an attack that killed 21 people.) Insurance fraud?

My personal favorite theory, though, is the one about the humanoid snake.

“It was said that the owner [of Kimball Plaza] possessed a snake which he kept locked up and hidden somewhere under the establishment,” wrote Blaise Sigue, Lou Pasilan, and Jo Zulita, who all grew up here and somehow survived childhood with these kinds of urban legends. The snake supposedly brought luck, which is why the owner kept it, never mind that people who went missing in the mall were believed to have been fed to it. Eventually the snake escaped, coiled itself around an electrical post, brought it crashing down, and sparked the fire that destroyed Kimball Plaza. At least that’s what people claimed they saw.

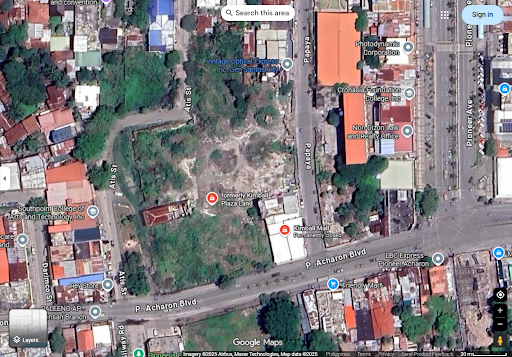

Kimball Plaza used to sit right there on Papaya Street, next to Pioneer Avenue, which was the place to be back in the day. By the time I moved to GenSan for college in 2011 the mall was long gone, just a patch of ground where something used to be. Here’s what it looks like now on Google Maps:

The site is marked as “formerly Kimball Plaza Land,” a wide, barren stretch framed by Papaya and Atis Streets, its surface a pale mix of dirt, weeds, and scattered debris. The lot just sits there surrounded by small houses and aging buildings, the whole neighborhood frozen somewhere around 2002 while the rest of GenSan moved on. SM and the newer malls have pulled the center of gravity elsewhere, leaving this corner of GenSan to its memories, ghosts, and snakes.

There’s even a little digital label that says “Permanently closed,” which is the saddest two words you can slap on a place that people still can’t stop talking about. Here’s the thing: everyone still calls that area Kimball. Tell a tricycle driver you’re going to Kimball, and he’ll nod and know exactly where you mean, even though there’s nothing actually there anymore.

I can’t help but be charmed by this stubborn little piece of history. The mall burned down over twenty years ago, and yet Kimball refuses to leave the local vocabulary. Is it just convenient shorthand? Or have people decided, collectively and without ever discussing it, that a street named after an invisible mall makes more sense than one named after a common fruit? Either way it’s a reminder that language and history are tangled up together, inseparable.

Food historian Doreen Fernandez writes about this kind of thing in Palayok: Philippine Food Through Time, on Site, in the Pot. In the book, Fernandez traces how Chinese, Spanish, and American influences show up in Filipino food. It’s all right there in what we call them: pansit, relleno, Spam. The names tell the story of our colonization, cultural exchange, and transformation—our history, in short, served on a plate. We are what we eat, sure, but we’re also what we call what we eat.

I left GenSan in 2018 to return to Davao, but when I think about my college years, I’m always standing at Kimball—a place that doesn’t exist—waiting to catch a tricycle. The driver pulls up and asks, “Diangas?”

“Diangas” is what people call the new downtown area, except it’s not really new. It’s a clipping of “Dadiangas,” which was the city’s original name, given by the Blaan people who were here first. It’s also what they called the thorny trees that used to grow everywhere.

In the early 1900s, as part of some grand resettlement scheme under Manuel Quezon, the government decided to relocate people from Luzon and Visayas down south. General Paulino Santos (yes, that General Santos) led the first wave. These migrants brought their languages with them, and now GenSan is this linguistic free-for-all. Walk into any mall (a real one, not a ghost one), and you’ll hear Tagalog, Ilocano, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Maguindanaoan, Blaan—sometimes all in the same conversation, sometimes all from the same person.

“Diangas” is a beautiful contradiction. It wants to sound modern, but it’s clinging to the past. So when you’re standing at Kimball—which isn’t there—and a tricycle driver asks you “Diangas?”—which is and isn’t the new downtown—just know that he’s not simply asking where you’re headed. He’s handing you the whole story of the city, compressed into one word, delivered casually, as if it’s the most normal thing in the world.