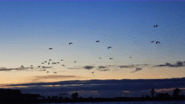

Stars still shone in the sky when I and other travelers rode an outrigger boat bound for the wetlands of Sasmuan, Pampanga. As our boat cut through still waters and oranges and blues began to brighten the sky, we saw dark spot upon dark spot flying above us.

These were migratory birds passing by or taking a respite from the harsh winters of countries in the West like Russia before they go farther on their journeys. The waters that surrounded us and the mangrove forest we were heading to are part of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, the international “highway” for migratory birds.

After about 40 minutes on the water, we pulled up to a stretch of mangroves that seemed to float on the river, reachable only by a narrow wooden walkway. This was our destination: Sasmuan Bangkung Malapad Critical Habitat Ecotourism Area – the heart of the Sasmuan Pampanga Coastal Wetland.

We stepped onto the walkway, mangroves thick on either side. The 300-meter bridge offered only brief glimpses of the forest canopy. The place was quiet except for our footsteps and the occasional birdcall.

At the end of the walkway we found an open-air hut with an uninterrupted view of the mangrove-lined bay and Bataan’s mountains on the horizon. Whiskered Terns, Barn Swallows, and other species flitted above the greenery.

As the sun rose, the mangroves shone a golden-green hue. Birds drifted through the air at different heights – some low, near the leaves, others high above. I watched the scene unfold from the hut.

It was at that moment that I realized, more than just being part of a global flyway, Bangkung Malapad was a sanctuary, a rest area for birds amid their long journeys. Here, they get to warm their wings in tropical weather and nourish themselves with fish, crustaceans, mollusks and other organisms teeming in the mangroves and nearby mudflats and waters. Should there be strong winds, the birds can take shelter among the mangroves as well.

Sasmuan’s tourism officer and conservation advocate Jayson Salenga said that Bangkung Malapad and the rest of Sasmuan’s coastal wetlands regularly support 20,000 or more waterbirds. During the migratory season (around November to March), the numbers climb higher. The 2021 Asian Waterbirkapad Census counted 80,000 birds from 63 species.

Drinking in the sight of the occasional birds, mangroves, and the morning sun, I felt the place was a haven for me as much as it was for the birds.

Bangkung Malapad was not always this peaceful, though. In fact, it was born from the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption. Its islet, now lush with mangroves, came from the sediments spewed by the volcano. The once-barren landmass grew lush with mangroves as birds that rested there brought seeds. Others were planted by locals.

The Kapampangans had a stronger, renewed commitment to protect the mangroves in the area after barangays near the ecotourism site were spared by Typhoon Glenda in 2014. It was the islet of mangroves that acted as a buffer against the wind and waves. The mangroves were life-saving; local patrol ensured none of the trees were cut.

Protecting the mangroves helps sustain local fisherfolk’s livelihood as well, as mangroves are spawning grounds for fish and other species, with some staying in the mangroves before moving to deeper parts of the sea once they have grown. Bangkung Malapad in particular is home to a vulnerable mangrove species known to support a considerable and diverse number of fish and crustaceans.

Another special thing Jayson shared was that Bangkung Malapad helps curb pollution in Manila Bay, with the strip of mangroves lining the bay’s waterway.

Years after my visit, the Sasmuan Pampanga Coastal Wetland was recognized as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, an intergovernmental treaty that provides the framework for national and international action in conserving and wisely using wetland resources.

This means that Sasmuan’s wetlands and its corresponding 3,667.31 hectares are globally acknowledged to be important to the environment and culture, among others. The treaty also enjoins the government to strengthen the management and protection of the site. This will help ensure Sasmuan’s wetlands continue to protect vulnerable and endangered species in the area, as well as safeguard local communities and their livelihoods. And, with conservation measures in place, the wetlands will continue to be both a rest area for birds and for any visitor looking for a scenic respite.