“We don’t want tourists. In fact, we don’t need them here. We don’t want people walking in here disrespecting nature, our people, and our culture,” said an Applai-Igorot from whom we were purchasing some souvenirs before we departed Sagada—Ganduyan, as its traditional Kankanaey name goes—a quaint and popular town in the Mountain Province in Cordillera.

I was honestly dumbfounded. I didn’t know how to feel or react.

“Sorry po,” I politely said, an apology offered on behalf of tourists, I suppose. His words stayed with me, making me skip traveling to this place for a while.

It was in 2019 when I first set foot in this town. My impression of the Igorot – the indigenous people of the Cordillera – during our first encounter was that they were stern and distant, away from the trademark warmth and hospitality Filipinos are known for. Admittedly, my first visit was rather quick; I did not have enough time to appreciate Sagada’s beauty or understand where the local seller was coming from — a mistake on my part.

A Shift in Perspective: A Pandemic Return

The following year, the COVID-19 pandemic hit and put the world to a halt. It was a reset in the tourism industry – and for me, too. I took it as a time to reckon with my ways and intentions for traveling, and made efforts to understand the concept of sustainability deeper, encompassing aspects beyond ecological.

In 2022, I had an opportunity to visit Sagada again, though still with those first impressions sitting at the back of my mind. We braved the long drive from the city to the Cordilleras one November evening, not knowing that it would be one of the most impactful, memorable, and immersive trips I’ve ever had.

We explored its top attractions, including Blue Soil, Echo Valley and hanging coffins, Sagada pottery and weaving, and Marlboro Hills. We also dined in well-known restaurants in town and tried dishes the locals take pride in serving.

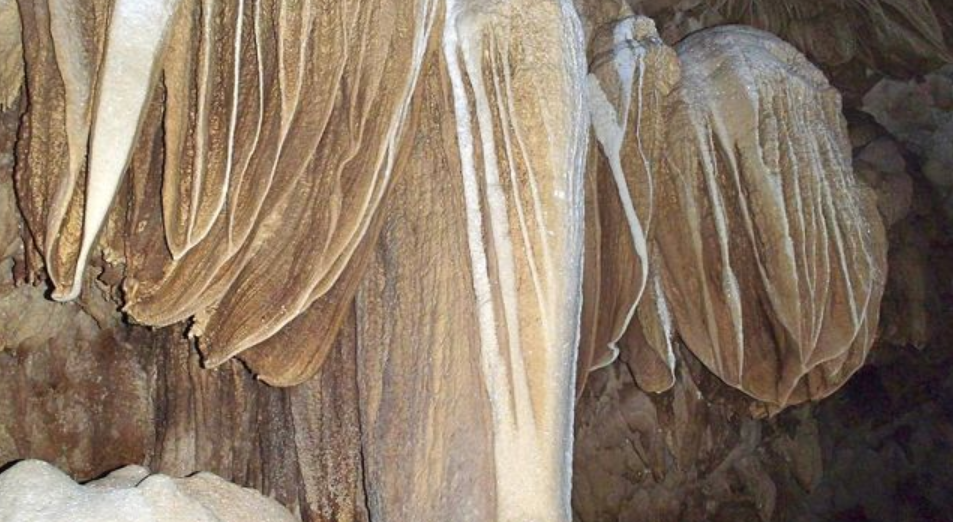

We also took to destinations not typically present in the usual tourist itinerary like Kamangwit Eco Park, also known as South Park; Balangagan Cave, and the Ganduyan Museum. These destinations, along with the locals, opened up a brand-new perspective for me.

The Museum Visit That Made a Difference

To me, visiting the Ganduyan Museum first before exploring Sagada’s other renowned attractions would be ideal. The only museum in town, it made us understand everything about Sagada better: how the place came to be, the Applai-Igorot and their culture, and their way of life past the tribal wars and colonization — everything. Listening to Lester Aben’s—the son of the museum’s creator, the late Cristina Aben—accounts of his ancestors’ life with pride and might, felt like an extensive walk-through of Sagada’s history.

It made me understand their call for responsible tourism. It only makes sense to want to preserve their beloved homeland; they shed sweat, blood, and tears protecting their heritage against the colonizers ages ago. Refusing to embrace capitalism and modern-day colonialism means preventing its negative consequences on their culture and people.

To do this, locals put in place a systematic way of touring guests, making sure every trip is strictly guided by a local who doesn’t just know his way around but is also equipped with a deep knowledge of their roots, their culture, and destinations. For the Applai-Igorot people, tourism is more than just a livelihood. It is also a way of preserving their heritage and raising visitor education.

I stepped out of the museum seeing things differently, leaving my first impression of the Igorot people behind.

We found ourselves keen on keeping our hands off the jars and hanging coffins in burial sites, and staying quiet as we made our way to Echo Valley. We learned that in traditional burial practice, locals would only scream in the valley to announce someone’s passing and burial, and thus we didn’t dare to do it.

We remained silent during the long walk to Marlboro Hills for its glorious sunrise – no loud music, no resounding exchanges, only warm smiles traded with locals as they handed us a warm cup of champorado.

In restaurants, we casually engaged in conversations with owners about their delicacies and the unique touch they put on dishes to keep them authentic. We walked around town in modest clothing. Every time we arrived at our inn or homestay, our hosts would smile and we’d reciprocate. Whenever something or someone piques our interest, we’d always ask permission before flicking the camera shutter. We learned how and when to put the camera down and be in the moment. At a gathering, we danced with the people, understanding what the movements mean. Things went like this for the entire week of our visit. Sagada and its people grew on me – an adoration that came with better understanding and appreciation.

My return to Sagada made me realize that it’s not that the Igorot don’t want tourists at all. They only want us to understand that it’s not the locals’ responsibility to adjust and adapt their ways to cater to visitors. Doing so would mean losing their identity as well. To preserve their culture would be to stick to their own way of welcoming and entertaining tourists, without risking their identity, and with us, visitors, learning to adapt, too.